The scenery began to change as I left the agricultural flats of Taranaki and ventured deep into the Forgotten World Highway. Slowly, the fields began to undulate and I was soon immersed in temperate rainforest. My destination was Tongariro National Park, an alpine region in the middle of the North Island that’s famous for its ski resorts and dramatic scenery. Imposing volcanoes stand proud on this impressive landscape, constantly asserting their dominance with eruptions as recent as 2007. As I approached the area, the jagged, gigantic profile of Mount Ruapehu presented itself in the distance, welcoming me to its sacred fields.

Despite the association of volcanism with soil fertility, the area immediately surrounding the active Mt Ruapehu, Mt Tongariro and Mt Ngauruhoe is paradoxically barren. Here, the soils are composed of loose layers of pumice rubble, accumulated over years of recent and ancient eruptions. At 1,200 m high, the rainfall here is strong and frequent enough to strip the soils of vital nutrients, yet the water drains straight through the porous ground like a sieve. Harsh alpine winds and the oppressive winter cold prevents substantial plant growth from accumulating. It’s in these poor conditions that specially adapted carnivorous plants have found their niche.

Soon after embarking on my three day trek on the Tongariro Northern Circuit, I noticed that the sides of the trail were the ideal habitat for sundews. Drainage ditches had been cut, allowing water to accumulate and support a range of swampy plants. I recognised the abundant bright purple blooms that littered the trail as Thelymitra sun orchids, a species that favors the waterlogged soils commonly associated with some sundew species. With some searching I quickly located the first carnivorous plant of the trip – a multiforked Drosera binata growing amongst the sedge.

Not long after, I noticed a strange patch of colour in a depression ahead. A striking colony of hundreds of Drosera binata T-form plants had established themselves, their bright-red dew-laden leaves gloriously catching the low rays of the morning sun! As it was the middle of summer, the plants had sent long flower stalks high above their sticky traps. Most specimens of this species do not self-pollinate and require insects to cross fertilise their flowers – the height of the flowers prevents pollinating insects from inadvertently getting trapped. In winter, the species enters dormancy, forming a tight bud that rests below the insulating snow. The species is almost always associated with waterlogged soils, whether it be in a swamp or hanging off the seepages of a road cut.

As the path continued towards the conical profile of Mt Ngauruhoe, a sprawl of dry river beds left their impression in landscape. Flowing above ground only in flood, the smaller rivulets of the area have since retreated below the surface. Still, their subterranean presence wets the soil enough to support populations of Drosera arcturi and Drosera spatulata on the edges of the banks.

Drosera arcturi is one of the few species that are found exclusively in alpine environments, calling the mountains and southernmost lowlands of Australia and New Zealand home. Their thick leathery leaves resist the cold well with a reduced surface area to volume ratio that prevents freezing. Like its forked-leafed counterpart, D. arcturi forms a non-carnivorous resting bud during the snowy winter. The species often has only two or three healthy leaves at a time – there’s no point wasting energy making a large rosette when a sudden frost could snap them off at any time. Unfortunately, this also makes adult specimens rather rugged-looking and hard to photograph. Seedlings, however, are cute as always:

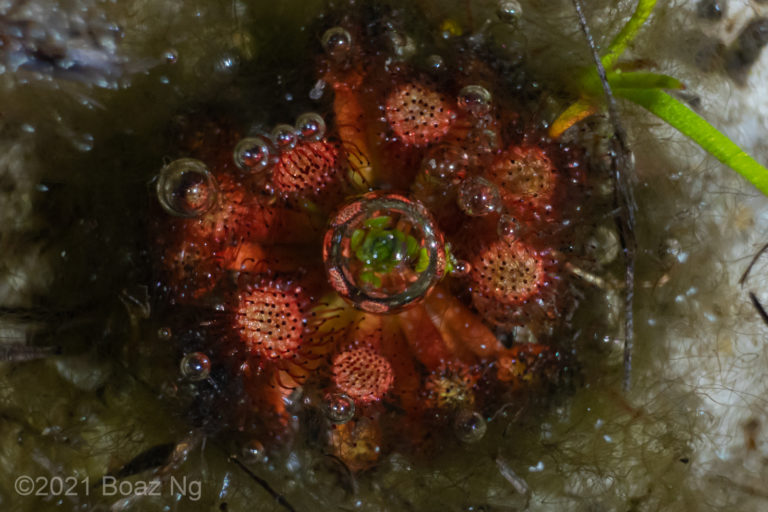

Growing alongside them were tiny specimens of Drosera spatulata. The plants here represent the only genuinely alpine adapted variation of the species I’ve ever seen. The local subspecies are truly dwarfs – flowering sized adult plants span no longer than one or two centimeters in diameter. The flower stalks are fleshy and short, each producing a small cluster of flowers. Instead of producing a longer chain of blooms, the plants send out multiple stalks concurrently.

Presumably, the compact growth habits of the local variety are adaptations for the harsh alpine conditions. Miniature leaves reduce the amount of leaf surface that’s exposed to the cold air. The bright red colouration acts as ‘sun-screen’ against the damaging high-altitude UV rays. The short flower stalks may prevent them from otherwise snapping in the strong mountain winds. Having multiple stalks at once allow the plants to have many flowers without needing to increase the length of the stalk. Unlike D. binata, this species is self-pollinating so having blooms close to the sticky leaves does not present a problem.

It was lovely examining the cold-adapted traits of three of New Zealand’s alpine growing species. Unbeknownst to me at the time was that two miserable, wet, windy, freezing and exhausting days of hiking through exposed volcanic wasteland were to follow. In the end, it was still a privilege to observe these resilient carnivorous plants thriving in this oppressive landscape.

– Boaz

(New Zealand looks better in the rain anyway)